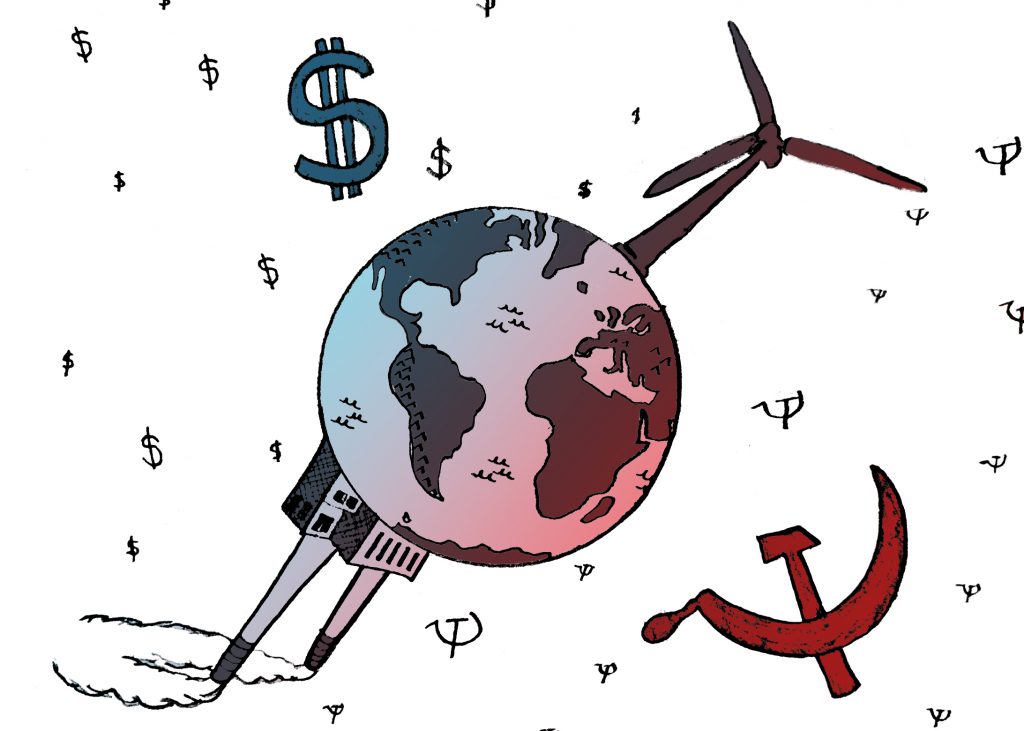

To the novice environmentalist, the U.S. fossil fuel industry is an unfashionable and soon-to-be bygone market. President Joe Biden and his White House National Climate Advisor, Gina McCarthy, aren’t blankly idolizing renewables either. Since January, the Administration gave several blows to oil and natural gas firms, pausing new extraction leases on federal land, revoking permits for the Keystone XL Pipeline, and halting drilling operations in the Artic (at least on paper).[1][2] During April’s international climate summit, the U.S. announced halving its greenhouse emissions by 2030 and becoming “carbon neutral” by 2050.[3] And with BloombergNEF projecting 58% of cars electrified by 2040, gas stations and providers will come to their demise as revenue diminishes.[4]

But the industry isn’t going to retire graciously – at least not empty-handed. U.S. oil production has nearly doubled since 2010, extracting 12.8 million barrels per day in 2019.[5] Producers are not drilling to cover debts; within the last decade, the price of gas has averaged $2.99 USD per gallon.[6] Even more scandalous, the explosion of natural gas consumption since 2000 has managed to overpower coal, nuclear, wind, and solar energy combined.[7]

Why is this happening? Aside from technological enhancements making extraction easier, corporations have been accelerating production as last-minute predatory capitalists. Oil executives have been aware of their environmental damage as far back as the 1970s, covertly employing scientists to study the rise of global temperatures.[8] Some firms have calculated the social cost of carbon – a subsidiary of Exxon Mobile estimated $75 (USD 1991) per metric ton in 1991.[9]

None of this has stopped the industry from drilling in 44.2 billion barrels of proven U.S. oil reserves or the 494.9 trillion cubic feet in natural gas still left.[10] In fact, with so much revenue left to make, the 2050 deadline presents more of a challenge as firms race to see who gets the last laugh.

The irony of anti-pollution measures incentivizing pollution has not fallen flat on environmentalists. German economist Hans-Werner Sinn coined this phenomenon in his 2012 book of the same name, The Green Paradox, although it is commonly referred to as “temporal leakage.”[11] Among academic circles, the negative externality is generally unavoidable and untreatable. That’s not going to discourage government regulators from trying to castigate opportunists. The question is, how far should the U.S. be willing to wage war against its own polluters?

First, examine a scenario where temporal leakage is unchallenged by regulatory bodies. Using 1970 as a reference point, global CO2 emissions have increased more than 145%, while the U.S. had a 46% increase at its peak in 2005.[12] Average global temperatures have also increased 0.66-0.75 degrees Celsius during this period.[13] From this alone, the U.S. owes trillions of dollars in environmental degradation and economic loss. While fossil fuel executives aren’t fully accountable for this, it’s unforgivable to see such stakes be knowingly downplayed. Even as green energy becomes more popular, Americans cannot afford to ignore ravaging acceleration for another decade.

The innate response is to apply “scorched-earth” measures mitigating temporal leakage at any and all costs; crippling carbon taxes, strict and immediate carbon capping, reducing heavy industry zoning, product bans, and more. We already have strict anti-exploitation examples in Morocco, where the government banned plastic bag production, imports, and sales nationwide in 2016.[14] Or one can look at the island nation of Palau, which barred fishing from 80% of its marine territory to strengthen conservation efforts at the population’s dietary expense.[15]

Attacking the carbon footprints of billion-dollar conglomerates like Exxon Mobile or Chevron is an obstacle of its own. Assuming the White House can outwit the $112 million (USD 2020) lobbying campaign from the energy sector and make the measures politically feasible, major polluters can simply move their emissions – and well-paying work – overseas.[16] Since 2001, Americans have lost 3.7 million manufacturing jobs to China, thanks (in part) to lower environmental standards.[17] Scorched-earth measures are not only counterproductive to climate abatement, but economically suicidal.

Instead, the U.S. should embrace more moderate and “Machiavellian” strategies, that is to say, measures that can coerce producers to relax overproduction without being overtly oppressive. For instance, had the White House played their moves right, they could have enacted exit taxes and high carbon tariffs on imports well before announcing their 2030 deadline, removing incentives to emigrate and nudging firms to take the brunt of Biden’s domestic agenda as their best business option.

Acting “Machiavellian” doesn’t mean secretly plotting away from public view. Utilizing the “boiling frog” fable, where polluters do not perceive their deaths until it is too late, won’t work because oil and gas executives already know they are public enemies. What it does mean is having the U.S. present a new level of assertiveness and premeditation fossil fuel companies had the privilege of not seeing all these past decades. It’s an approach we can currently afford.

Work Cited

[1] “Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.” The White House. The United States Government, 27 Jan. 2021. Web.

[2] “Executive Order on Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis.” The White House. The United States Government, 21 Jan. 2021. Web. 05 May 2021.

[3] Herman, Steve. “Biden Pledges Rapid Decline of Fossil Fuel Use by US.” Voice of America. 22 Apr. 2021. Web. 27 Apr. 2021.

[4] Silverstein, Ken. “The Oil Industry Has More To Fear From Elon Musk Than It Does Joe Biden.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 02 Feb. 2021. Web. 05 May 2021.

[5] “US Oil and Gas Wells by Production Rate.” U.S. Energy Information Administration, 23 Dec. 2020. Web. 05 May 2021.

[6] “U.S. All Grades All Formulations Retail Gasoline Prices (Dollars per Gallon).” U.S. Energy Information Administration, 3 May 2021. Web. 05 May 2021.

[7] “U.S. Energy Facts Explained.” U.S. Energy Information Administration, 7 May 2020. Web. 05 May 2021.

[8] Hall, Shannon. “Exxon Knew about Climate Change Almost 40 Years Ago.” Scientific American. Scientific American, 26 Oct. 2015. Web. 05 May 2021.

[9] Wagner, Gernot. “Why Oil Giants Figured Out Carbon Costs First: Gernot Wagner.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 22 Jan. 2020. Web. 05 May 2021.

[10] “U.S. Crude Oil, Natural Gas, and Natural Gas Proved Reserves, Year-end 2019.” U.S. Energy Information Administration, 11 Jan. 2021. Web. 05 May 2021. <https://www.eia.gov/naturalgas/crudeoilreserves/>.

[11] Phelps, Edmund S., and Hans-Werner Sinn. “The Green Paradox.” The MIT Press. The MIT Press. Web. 05 May 2021.

[12] Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. “CO2 Emissions.” Our World in Data. Global Change Data Lab. Web. 05 May 2021.

[13] “World of Change: Global Temperatures.” NASA Earth Observatory. NASA. Web. 05 May 2021. <https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/world-of-change/global-temperatures>.

[14] Alami, Aida. “Going Green: Morocco Bans Use of Plastic Bags.” Environment News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera, 01 July 2016. Web. 05 May 2021.

[15] Cirilla, Ashleigh. “Palau National Marine Sanctuary Goes Into Effect.” The Pew Charitable Trusts. 1 Jan. 2020. Web. 05 May 2021.

[16] “Oil & Gas Lobbying Profile: Lobbyists.” OpenSecrets. The Center for Responsive Politics. Web. 05 May 2021. <https://www.opensecrets.org/federallobbying/industries/lobbyists?cycle=2020&id=E01>.

[17] Adams, Cathalijne. “U.S. Job Loss to China Swells to 3.7 Million.” Alliance for American Manufacturing. 14 Sept. 2020. Web. 05 May 2021.